When Allison and I left the hotel early the next afternoon, we found ourselves in a completely different world. Although the streets had been empty and silent when we arrived late the night before, they were now packed with people going about their daily lives. The area we were staying in, Karol Bagh, was not particularly touristy, and we saw only a couple of people who appeared to be European or American, or who even looked like tourists at all. This was a pleasant finding, and it made the experience that much more real.

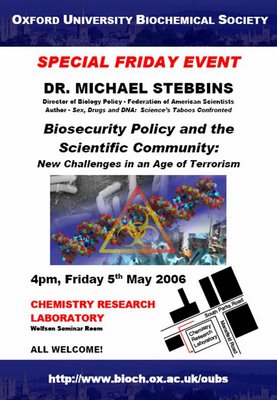

The sun, almost directly overhead, was bright and warm, but not unpleasantly so. It was a nice change from the dreary weather of England, and I enjoyed wearing a short-sleeved shirt outside for the first time in months. The dust that I had found so striking the night before was still present the next day, and it would be ubiquitous throughout Delhi.

March 25th was our first full day in India, and since the rest of our group of six would not be arriving until the next day, Allison and I spent the day just taking in India. And, there was a lot to take in. The fast-paced automotive chaos of the airport highway translated here to streets crowded mostly with people and autorickshaws, but also with cars and the occasional cow. The poverty was pervasive, but not necessarily overbearing. Most of the people seemed busy with some purpose, although I saw several people who clearly lived on the streets and faced a grinding destitute poverty. Since almost everyone we saw was probably financially poor, though, it’s impressive that some of the poverty was able to stand out at all.

Although we generally kept to ourselves, Allison in particular seemed to attract people’s attention. It wasn’t necessarily because her skin was white or because she was wearing westernized clothes, although those were surely important factors here. In fact, she was one of the few women at all that we saw that afternoon. I still don’t know if this was because of the time of day or because of where we were, because we did not observe this same phenomenon everywhere we went.

We walked about fairly aimlessly, although carefully keeping track of our location relative to the hotel. Each street we turned down seemed more crowded than the last. India was inescapable: the hoards of people, the vehicles, the noises, the enticing smells coming from the street food, the signs piled upon signs covering the sides of buildings. There was an energy running through the place that was hard to ignore. It was absolutely invigorating.

After we felt like we had absorbed enough of our surroundings, we decided to head toward New Delhi for a change of scenery, and hopefully to find some food. We had so far only seen street food, and although it was tempting, we were both pretty serious about avoiding anything that could make us sick (this turned out to be a virtual impossibility). We hired an autorickshaw to take us to Paharganj, an area about halfway between Old and New Delhi. Rickshaws, small three-wheel vehicles with meager two-cylinder engines, instantly became our preferred means of travel, mostly because of the price. We negotiated the price for this trip down to Rs 35, about 0.40 GBP, which was comparable to what we would pay the rest of our time in Delhi, and was probably about half as much as a taxi would have cost. Autorickshaws were cheap, simple, and all over the place. This last characteristic was clearly a product of the first two which have led to rickshaws now dominating the roads in many parts of India. Many people consider them to be pests, and it is expected that as the standard of living increases throughout India they will slowly disappear as more people can afford their own motorcycles. If riding in a car in India was stressful, riding in an autorickshaw was absolutely terrifying (probably like driving a go-kart down a Texas highway full of full-sized pickup trucks)—but only at first. I came to enjoy it as just another part of the experience.

Autorickshaws in Delhi traffic.

Autorickshaws in Delhi traffic.Paharganj felt more ancient that Karol Bagh, but also slightly more touristy, as we found ourselves in an area full of European hippie backpacker tourists, a demographic we ran into time and time again throughout our time in India. We didn’t find anything to eat, though, so we headed further toward the center of New Delhi, to Connaught Place, an enormous traffic circle made up of two concentric circles, intersected by close to ten busy streets. It was nearby, so we decided to walk. On our way, we met a boy, probably just a few years younger than us, who was very interested in talking to us to “practice his English.” He had long slicked-back hair, wore sunglasses, and sported more stylish clothes than we were used to seeing in India. He spoke English well, almost flawlessly, which we were not used to. Although almost everyone we interacted with spoke some English, it was generally very broken, and often mixed with Hindi. I’m still not exactly sure how widespread English really is in India, and I still have a feeling that most people in India probably don’t speak English, or at least don’t want to. Regardless, the people we needed to communicate with to get around invariably spoke enough English for us to get by.

Our new friend seemed very concerned with our wellbeing, and he

highly suggested that we check out the “government tourism center” across the street to get a “free map.” Although he was nice to talk to, it was clearly a ploy to take us somewhere for him to earn a commission (since I still have not seen a “government tourism center," although there is a place that suspiciously sports such a label in the map above). We passed on his offer, and continued on to Connaught Place. Within a few minutes he was back again, or so I thought at first. It was actually a different boy, but wearing almost exactly the same uniform. He had the same story: he studies at the local university, he enjoys practicing his English by talking to tourists, and he really thinks we should go to the government tourism center to get a free map. We ran into versions of this same character several times, culminating in a group of about ten of him, all trying at once to get us to go to the tourism center they were pointing at.

A map of Delhi. During our first day, Allison and I basically made a triangle, starting at Karol Bagh in the northwest, continuing through Connaught Place to India Gate in the center/east, turning north toward the Red Fort, and then heading westward back to the hotel.

A map of Delhi. During our first day, Allison and I basically made a triangle, starting at Karol Bagh in the northwest, continuing through Connaught Place to India Gate in the center/east, turning north toward the Red Fort, and then heading westward back to the hotel.At Connaught Place, we finally found a restaurant that met our still overly stringent requirements, and the food was absolutely delicious, which I found to be a common theme throughout my travels in India. I had a mutton (goat) dish, along with some rice and naan (bread). I learned to eat in the traditional style, mixing my meat and rice together, and using my naan as both a utensil and a food. Allison had a mushroom masala, which was also very tasty. The vegetarian food in India was the best I have ever had, and it was often better, or at least more interesting, than the meat dishes: if there is anywhere I would consider being a vegetarian, it would have to be in India. I had a bottle of Kingfisher beer (one of the only beers widely available in India, a country that until recently was still widely prohibitionist) with dinner. It was a great first meal for the trip, although what was meant to be a late lunch turned into an early dinner because it had taken us so long to find a place to eat.

After lunch/dinner, we walked around (literally) Connaught Place, and then took an autorickshaw to India Gate, a large monument in the center of town. Since it was a Saturday night, we found the surrounding parkland (a surprising find in itself in the middle of Delhi) full of picnicking families, giving it a lively carnival-like atmosphere. Our autorickshaw driver had apparently followed us around India Gate, and eventually he convinced us to let him take us to Old Delhi proper. There, we had a great view of the Red Fort, which is brightly lit up at night. We spent most of our time, though, touring a

Jain temple. I found Jainism to be one of the more interesting local religions, as it focuses on extreme nonviolence and vegetarianism, and one of its central tenants is the intrinsic value of all living things. Because its followers are not allowed to hurt even a fly, some of the most devoted among them wear face coverings to prevent themselves from accidentally breathing in or swallowing (and killing) an insect. In that same tradition, this particular temple featured a bird hospital. We explored the nearby areas, and also observed a Sikh temple. Interestingly, on the side of the temple were the five main tenets of this particular sect of Sikhism, written out in English. One of them was the use of special underwear to prevent adultery. This raised more questions than it answered.

Sometime after about 10:00 pm or so, we decided that it was time to head back to the hotel. We went to find an autorickshaw, but all of the drivers were clearly offering only highly inflated prices. Although I turned him away at first, we were approached constantly by a particularly persistent cycle-rickshaw driver. Neither of us really wanted to take a cycle-rickshaw, not just because it would be much slower, but because there’s something unsettling about exploiting someone else’s manual labor for personal transportation, especially when that person is obviously struggling and appears emaciated. The price was so much better, though, that his offer was tempting.

“How long will it take?” I asked.

“Twenty-five minutes. I’m very fast,” he responded.

Allison and I hesitatingly got in the rickshaw, something we would soon come to regret and a mistake we would not repeat. The ride started out harmlessly enough. Our driver was very friendly, and he pointed out several sights along the way. He was from Nepal, and he had moved to Delhi to make money to send his family back home. As the ride began to draw out past the twenty-five minute mark, he became quieter, and the city seemed to slowly clear out until it was almost empty. Although they were present in the day as well, animals roamed freely at night, particularly cows and stray dogs. I never thought that I could find anything scary about a cow, but as we passed through a small herd in the middle of the dark nighttime street, something about their big black penetrating eyes staring back at me did little to put me at ease. Still, the cows were just going about their own business, mostly looking for food. The cows in Delhi looked malnourished and skinny and from what I can tell subsisted mostly on garbage.

A cow walking through the streets of Delhi.

A cow walking through the streets of Delhi.As the night dragged on, we saw more and more people sleeping on the side of the road. In some places, the whole sidewalk was covered with people. Although the weather was not bad for staying outside, the sight of such poverty was truly shocking, and many of the images are still frozen in my mind.

Sometime around the first time our driver stopped to ask for directions, roughly an hour into the trip, brilliant bolts of lighting began to light up the night sky. Eventually heavy deliberate drops began to fall, but the promised storm never materialized, which was fortunate for us. It was still the dry season, and this was the only time we experienced rain during our trip. Still, the roads seemed to become darker and steeper and our situation more hopeless as our driver stopped increasingly frequently to ask for directions. For a while he clearly had no idea where he was going.

The Hotel Indraprastha never looked better than when we finally arrived that night, approaching two hours after our time of departure. Although it was after midnight when we returned, we discovered the hotel’s rooftop café and had a late dinner there. The scenery was beautiful, the atmosphere was relaxed—complete with candlelight—and the food was impressive. Combined with a cold Kingfisher beer, it was the perfect way to end my first day in India and prepare for another.